Home / Elections / Assembly Election / News / Brand Akhilesh Yadav and the American style of campaigning

Brand Akhilesh Yadav and the American style of campaigning

Apart from our elections, even the campaign machinery has also become more American

)

premium

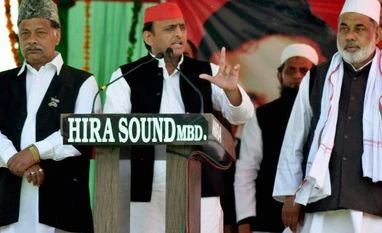

Samajwadi Party President Akhilesh Yadav addressing an election rally in Moradabad (Photo: PTI)

Last Updated : Feb 13 2017 | 4:54 PM IST

The 2014 general elections represent a watershed in the Indian electoral history in many ways. For one, it changed forever how campaigns are conducted in the country. The Lok Sabha poll campaign saw the then Gujarat chief minister, Narendra Modi, creating a parallel campaign machinery outside of the party to take his word to the people. His campaign to become the Prime Minister had, in fact, kicked off even before the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) named him its Prime Ministerial candidate.

Citizens for Accountable Governance (led by political strategist Prashant Kishor) helped Modi run a political campaign that could have given any MNC giant a run for its money. Through his 360-degree campaign, Modi reached out to disparate voters using their own communication mediums. What made it stand out was the campaign’s focus on modern technology – social media platforms like Facebook, Twitter and WhatsApp were used extensively and effectively to create a cult following for Modi and turn the election into an almost Presidential campaign. The result: Narendra Modi seemed to be the only candidate around.

Lessons from this campaign have been learnt by other political parties as well – some more than the others. Later, similar ways were used in Delhi by the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP), and in Bihar by Nitish Kumar, who built an unlikely alliance with his long-time bête noire Lalu Prasad, took his own message of good governance to the people, and returned to power with a landslide victory.

Sensing how political communication had changed, Chief Minister Akhilesh Yadav also decided to adopt the new paradigm. The process started in 2015, when he first met Gerald J Austin on October 31, 2015. Austin had been leading Democratic Party campaigns in the US for decades and had worked on campaigns for former US Presidents like Jimmy Carter, Bill Clinton and Barack Obama. The famous campaign strategist told the Economic Times that he couldn’t set up base in India owing to his age (he is 72 now) but could help train political associates and supporters.

Later, six members of Yadav’s team travelled to the University of Akron in Ohio and attended an international fellowship programme for two months that coincided with the US presidential polls in 2016. The team learnt about campaign techniques and also about voter micro-targeting.

Even as his party colleagues were getting trained in the US, Akhilesh Yadav also roped in a Harvard University professor, Steve Jarding, to help the Samajwadi Party design a campaign for the elections in UP that are now underway. This was done in mid-2016. Jarding also served as a campaign manager and political strategist to the Democratic Party in the US. His other clients included Hillary Clinton, Spanish PM Mariano Rajoy and former US Vice-President Al Gore. Brought on board by the UP CM in the capacity of a political consultant, Jarding helped Yadav redesign his party’s social welfare schemes.

Jarding advised Yadav that while his programmes were good, there was some confusion among voters about whose scheme they were – the centre or the state. Jarding and team did a survey across UP and concluded that Akhilesh Yadav’s clean image and connect with the youth offered an opportunity. In the ongoing seven-phase Assembly elections in the state, these aspects form the cornerstone of the Samajwadi Party offering in a presidential-style campaign.

There have been specific minor-campaigns that have been done by the Samajwadi Party to counter any negative perception. One of these involved Akhilesh Yadav projecting that all of UP was his family. This was done to counter the perception that his party was only serving the interests of his clan.

When the ugly battle between him and his uncle for control over the party was feared to damage his image, specific videos showing Yadav’s respect for his father were shared on different social media platforms.

To burnish his development and good-governance credentials, the campaign theme of ‘Kaam bolta hai’ was created. As elections got closer, schemes that had been in gestation for some time were finally launched with slick advertising campaigns. Journalist Sreenivasan Jain visited the official war room of the Samajwadi Party in Lucknow and found a team that included a lyricist, a former media professional whose team was tracking news as it unfolded, and a campaign strategist who doubled up as a technologist. This was a modern, hi-tech, political war-room that was helping take Akhilesh Yadav’s ‘kaam’ to the UP voter.

In another war room elsewhere, Jain met Advait Vikram Singh, a former student of Jarding who introduced Akhilesh Yadav to the Harvard professor. Singh claims he had no references to help him get to the UP CM but Yadav was so receptive that he ended up hiring Jarding. In this war room, a large number of telecallers were furiously making calls across UP, trying to gauge public opinion on an issue or question. These surveys went to the level of a constituency and the findings were then used by the party to identify the weak points so that any corrective action could be taken.

Information on trouble spots was then fed to the party and a team of 'persuaders' then visited these spots to subtly tilt the public opinion in favour of Akhilesh Yadav. These ‘persuaders’ do not inform the public that they officially work for the Samajwadi Party.

Jain’s team also visited villages and found an on-ground team of women was trying to push government schemes and helping reinforce the belief that the money for the schemes was flowing from the Akhilesh government. The reporter also called up the helpline numbers 108, 100 and 1090 to verify their functioning. The helpline 108 provides villagers with an ambulance service and 100 is to get help from the state police.

One of the weakest points for Akhilesh Yadav's government in the year 2014 was the poor law and order situation in the state. Women were said to be unsafe in particular and the helpline 1090 was set up to help women. The reporter found all the helplines responsive in her test calls.

Like any corporation, Team Akhilesh has identified Brand Akhilesh as its strong point and it also works on a 360-degree campaign to ensure narrative dominance and political success.

Tales of a young school teacher travelling from village to village in UP on a bicycle asking people to vote for him are now part of the legend. The young Mulayam Singh Yadav later graduated to a jeep but had little money left for fuel. Helped by his brother Shivpal Yadav, the two would address a public meeting and then ask those present to help them to buy fuel. This would take them to the next public meeting.

Election campaigns used to be about a large number of workers, political rallies and famous speeches. But election campaigns now include all these and also other parts. The new parts now sway more public opinion in favour or against a leader, a candidate or a party. Like many others, Akhilesh Yadav has embraced it. A professionally run campaign that takes the leader and his message to the voters.

In India, in 2017, this campaign machinery may not be enough, but it surely is essential to compete.

Twitter: @bhayankur