Marquee PE firms fail to get returns in Coastal Projects

The significant decline in revenue is because of delay in execution of some of the projects for want of various government/environmental clearances, geological conditions

)

Coastal Projects is a Hyderabad-based infrastructure company that rose to the status of a national player within a short span of time, but failed to deliver returns to its investors, including marquee private equity (PE) firms.

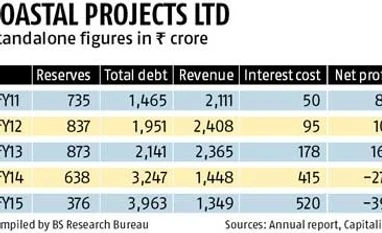

Between 2007-08 and 2011-12, the company grew from Rs 422 crore to Rs 2,408 crore, backed by investments by the Indian government in the infrastructure sector.

Coastal Projects carved a niche for itself using its expertise in underground excavation required for irrigation, power, hydroelectric and Metro rail projects. It was this strength that encouraged many PE firms to invest in the company.

Since the promoters, led by its chairman and managing director S Surender, were good at networking with governments, contracts kept coming in its way. The company’s current order book is to the tune of Rs 9,000 crore.

Spotting the opportunity early on, private equity firms led by Fidelity, Sequoia Capital and Deutsche Bank came in with a first round of funding in 2008. The second round happened in 2012 from other investors including Baring Private Equity Asia investment. All this happened when the company was doing quite well. This can be seen from the list of investors as well, including IDFC, L&T Infrastructure Finance, Multiconsult Trust, among others. The promoters hold 43 per cent stake in the company.

The PEs, which own 32 per cent in the firm, infused funds on top of liberal loans given by a consortium of 22 banks led by State Bank of India (SBI).

The problems for the firm started in 2010 when a large tunnel boring machine (TBM) got stuck in an irrigation project in Andhra Pradesh. The promoters and their funding partners looked at it as a freak accident and continued to pursue more projects by leveraging debt.

In 2014-15, the company stated: “There has been a significant decline of 39.2 per cent in the revenue from operations of the company from Rs 2,220 crore for FY15 as in CDR (corporate debt restructuring) projections to Rs 1,3,49 crore in FY15 being the actual turnover. This reduction was mainly due to the delay in execution of some of the projects for want of various government/ environmental clearances, geological conditions, technical problems in TBMs, delays in getting approvals from clients for change of scope of works and other related issues. Further, award of new orders got affected due to sluggish growth in infrastructure sector.”

On March 29, 2014 the company’s fund and non-fund based facilities amounting to Rs 4,435 crore were restructured under CDR.

The deterioration in the firm’s financial health continued as revenues started falling from Rs 2,365 crore in 2012-13 to Rs 1,349 crore in 2014-15, while the firm’s total indebtedness rose to Rs 4,224 crore.

As revenues fell, the net loss widened to Rs 446 crore in 2014-15 from a net loss of Rs 273 crore in the previous year. As the company’s downhill journey hastened, the lenders decided to invoke strategic debt restructuring (SDR) and fixed July 27, 2015 as reference date. Total debt exposure further rose to Rs 5,809 crore by the time the lenders approved SDR. Banks with major loan exposure to the company include SBI (Rs 708 crore), State Bank of Hyderabad (Rs 417 crore), Axis Bank (Rs 520 crore), Punjab National Bank (Rs 605 crore), and ICICI Bank (Rs 680 crore). The banks are in the process of converting a portion of their loans into equity using the RBI’s SDR scheme as they still got one year’s time to look for a new buyer taking the present management on board.

Will the new buyer, if any, help turn the company around? “One of the primary stated objectives of the SDR scheme is to try and revive the asset by removing operational/managerial inefficiencies. This was not the case in the CDR scheme and, hence, the SDR scheme specifically envisages bringing in a new promoter. Due to the prevailing macro-economic factors, it can be argued a new management would also not be able to bring a desirable turn around. However, if there is even a marginal increase in the market capitalisation of the company, the lenders would have some possibility of recovering some portion of their debt, which would not be the case otherwise,” said Nishant Beniwal, counsel, Khaitan & Co.

A couple of banks, when contacted, did not comment on the prospects of a turnaround for the company. E-mails sent to the promoters did not elicit any response.

The delay in implementing the SDR itself might not work negatively. To bring a turnaround, additional funds are required, which the lenders would not be willing to put in. In that case, the likelihood of a turnaround would diminish further. Therefore, lenders might tend to look for a new promoter at the earliest, says Nishant.

According to the analysts, given the prevailing macroeconomic factors, the recovery potential of infrastructure companies with huge debts is low.

“Infrastructure as a sector requires huge capital in the initial years that can only come from debt or equity. In the case of heavily debt-laden companies, there is no possibility of more debt and promoters would not want to infuse more equity till they are certain of cash flows. Thus, recovery would be on a slow path. The silver lining is that infrastructure demand will continue to rise and if projects are built on sound principles, there will always be offtakers/users,” adds Nishant.

More From This Section

Don't miss the most important news and views of the day. Get them on our Telegram channel

First Published: Feb 11 2016 | 12:32 AM IST