Manipur's young moving ahead in this isle of turbulence

This reverse migration received an impetus after the Armed Force (Special Powers) Act was lifted from the municipal areas of Imphal in 2004

)

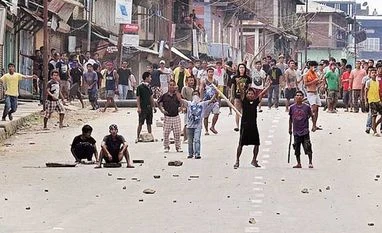

It is dusk and Imphal has been mobilised by a call for a 48-hour bandh across the state, spurred by the arrest of Ratan, former convenor of the Joint Committee on Inner Line Permit System (campaigning for a check on ingress into the state). In anticipation of a total market shutdown, locals stock their kitchens with vegetables and groceries.

In contrast, a group of young people, all of whom have studied and worked outside Imphal before returning to their home state, convene at the local hangout, Books and Coffee, seeming far removed from the tense political situation. Heisnam Shantanu, an alumnus of Delhi’s School of Planning and Architecture, is one of them. He recently returned to Imphal to work on bamboo architecture at H.O.O.D, an open-ended enterprise that uses bamboo and traditional building techniques.

“We’re creating homes, art installations and performance venues here,” says he. “Bandhs, economic blockades and political turmoil continue but I feel we need to get past these and move on.”

While Manipur continues to seethe with currents and counter-currents, he embodies the new wave of Manipuris, returning home after years of studying and working in what they still refer to as ‘mainland India’. Observers say in the past five years, Imphal has been a boom in the growth of small, creative enterprises — fashion boutiques, contemporary dance studios, cafes, bookshops, performance venues and more. “I’d say more such businesses have come up in the past five years than in the 15 years before that,” says Nelson Nameirakpam, editor of Horizon, a quarterly magazine on Manipur’s culture and lifestyle. He says many of these new businesses are concerned with improving of lifestyles. “I believe they reflect the changing aspirations of the youth in Manipur,” he says. “People like me are tired of complaining about the state of affairs. Not only do we want a change, in different ways — we’re all trying to be instruments of that change.”

To some extent, this reverse migration received an impetus after the Armed Force (Special Powers) Act was lifted from the municipal areas of Imphal in 2004. A couple of years later, the internet and telecom services saw vast improvements. “The internet opened many possibilities for locals. It became easy to connect with the external world and sell products and services online,” says Nelson. As the young slowly began to return to Imphal in larger numbers, there grew not only a sense of community among them but a market for the products and services they each had.

“Since I opened my café, Crossroads, in 2015, I’ve found my clientele is mostly local,” says Ibom Oinam. They say adversity spawns opportunity and Oinam has found his cafe become one of the few places for people to hang out after work in Imphal. Today, whether it’s a piano gig at Crossroads or a contemporary dance performance by local boy Surjit Nongmeikpam (he runs a popular dance studio in Imphal, called Nachom) or a day out in cycling with the local club — a growing number of willing and enthusiastic participants show up.

However, for all these young professionals in Imphal, political turmoil is a way of life, a frustrating one. “I keep my studio open during the bandh,” says Richana Khumanthem, a National Institute of Fashion Technology-trained designer who recently opened a boutique in Imphal. “Nobody comes but that’s okay.” Oinam describes how hard June was, when they had to write off 14 days because of bandhs. He describes what happened when he decided to host the cafe’s first performance, a blues piano gig by a local artist (also returned from Delhi to work in Imphal) in mid-August. A 48-hour bandh looked like it would disrupt his plans. “When the bandh was called off just in time for my gig, we dashed to Ima Market in the afternoon to get raw materials for the evening,” he grins. The gig was a great success and Oinam says his sales doubled that evening. He now wants to have performances at Crossroads every weekend, showcasing the region’s vast local talent. “Let’s see how it goes,” he says. “When you run a business in Manipur, it’s better not to make long-term plans but to live in the present!”

For some, it is business as usual in spite of the bandhs. “During the last bandh, our office remained open to all those who could make it,” says Nameirakpam. They all say they’ve learnt to assess how successful a bandh will be. “If it looks weak, I try and go to work like normal,” says Shantanu. “If it looks strong, I stay at home.” He is, like Oinam, Khumanthem and countless others, undeterred that his hometown is still not the easiest place to run a business: “Perhaps,” he says, “by choosing to return and work at home in spite of it all, people like me are effecting a quiet cultural revolution of our own.”

THE BIG BANDH THEORY

In contrast, a group of young people, all of whom have studied and worked outside Imphal before returning to their home state, convene at the local hangout, Books and Coffee, seeming far removed from the tense political situation. Heisnam Shantanu, an alumnus of Delhi’s School of Planning and Architecture, is one of them. He recently returned to Imphal to work on bamboo architecture at H.O.O.D, an open-ended enterprise that uses bamboo and traditional building techniques.

“We’re creating homes, art installations and performance venues here,” says he. “Bandhs, economic blockades and political turmoil continue but I feel we need to get past these and move on.”

Also Read

While Manipur continues to seethe with currents and counter-currents, he embodies the new wave of Manipuris, returning home after years of studying and working in what they still refer to as ‘mainland India’. Observers say in the past five years, Imphal has been a boom in the growth of small, creative enterprises — fashion boutiques, contemporary dance studios, cafes, bookshops, performance venues and more. “I’d say more such businesses have come up in the past five years than in the 15 years before that,” says Nelson Nameirakpam, editor of Horizon, a quarterly magazine on Manipur’s culture and lifestyle. He says many of these new businesses are concerned with improving of lifestyles. “I believe they reflect the changing aspirations of the youth in Manipur,” he says. “People like me are tired of complaining about the state of affairs. Not only do we want a change, in different ways — we’re all trying to be instruments of that change.”

To some extent, this reverse migration received an impetus after the Armed Force (Special Powers) Act was lifted from the municipal areas of Imphal in 2004. A couple of years later, the internet and telecom services saw vast improvements. “The internet opened many possibilities for locals. It became easy to connect with the external world and sell products and services online,” says Nelson. As the young slowly began to return to Imphal in larger numbers, there grew not only a sense of community among them but a market for the products and services they each had.

“Since I opened my café, Crossroads, in 2015, I’ve found my clientele is mostly local,” says Ibom Oinam. They say adversity spawns opportunity and Oinam has found his cafe become one of the few places for people to hang out after work in Imphal. Today, whether it’s a piano gig at Crossroads or a contemporary dance performance by local boy Surjit Nongmeikpam (he runs a popular dance studio in Imphal, called Nachom) or a day out in cycling with the local club — a growing number of willing and enthusiastic participants show up.

However, for all these young professionals in Imphal, political turmoil is a way of life, a frustrating one. “I keep my studio open during the bandh,” says Richana Khumanthem, a National Institute of Fashion Technology-trained designer who recently opened a boutique in Imphal. “Nobody comes but that’s okay.” Oinam describes how hard June was, when they had to write off 14 days because of bandhs. He describes what happened when he decided to host the cafe’s first performance, a blues piano gig by a local artist (also returned from Delhi to work in Imphal) in mid-August. A 48-hour bandh looked like it would disrupt his plans. “When the bandh was called off just in time for my gig, we dashed to Ima Market in the afternoon to get raw materials for the evening,” he grins. The gig was a great success and Oinam says his sales doubled that evening. He now wants to have performances at Crossroads every weekend, showcasing the region’s vast local talent. “Let’s see how it goes,” he says. “When you run a business in Manipur, it’s better not to make long-term plans but to live in the present!”

For some, it is business as usual in spite of the bandhs. “During the last bandh, our office remained open to all those who could make it,” says Nameirakpam. They all say they’ve learnt to assess how successful a bandh will be. “If it looks weak, I try and go to work like normal,” says Shantanu. “If it looks strong, I stay at home.” He is, like Oinam, Khumanthem and countless others, undeterred that his hometown is still not the easiest place to run a business: “Perhaps,” he says, “by choosing to return and work at home in spite of it all, people like me are effecting a quiet cultural revolution of our own.”

THE BIG BANDH THEORY

-

100s of bandhs every year

-

14 the highest number of bandhs in 2016 happened in June

-

Rs 4,970 cr loss of revenue because of bandhs and economic blockades in the state till date, according to the Poknapham News Service

- Rs 130-200 per litre and Rs 1,200-1,500 per LPG cylinder are the black market prices during bandhs

More From This Section

Don't miss the most important news and views of the day. Get them on our Telegram channel

First Published: Sep 05 2016 | 12:28 AM IST