Paying for past sins?

Lack of policy co-ordination post-Lehman caused our current predicament; let's not repeat history

)

Two data points were released on Budget day. At noon the finance minister indicated - to the relief of markets - that the 2012-13 fiscal deficit was contained to 5.2 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP), an impressive consolidation vis-à-vis last year.

At 5 p m that evening, GDP growth printed at a 15-quarter low of 4.5 per cent. The markets sighed in anguish. Sub-five per cent growth is unacceptably low, given the country's development and demography.

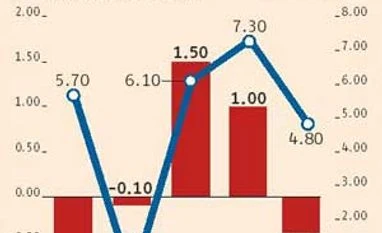

Surprisingly, nobody has connected the dots. A tightening fisc and slowing growth are seen as coincidental. Markets applaud fiscal discipline, but bemoan weak growth. But these are not independent phenomena. Instead, they are inextricably linked. Fiscal austerity impinges upon growth. A reduction in the deficit has a contractionary impact on activity. Europe, anyone? Furthermore, when that happens primarily by squeezing expenditures - where fiscal multipliers are larger - the growth-dampening impacts are more acute. On a cyclically adjusted basis, India's deficit was reduced by a whopping 1.5 per cent of GDP in 2012-13 - largely by squeezing expenditures. No wonder the slowdown was accentuated further.

Not for a moment am I suggesting the government should not pursue fiscal consolidation. Continued laxity would have triggered a ratings downgrade with devastating consequences for the economy. Nor am I attributing the slowdown entirely to the fisc. Growth began to slow much earlier on project execution bottlenecks.

But we must accept that fiscal policy is being forced to be, undesirably, pro-cyclical and is accentuating the slowdown. So let's not blame our woes on "global factors". Even as the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) is being goaded to cut rates to boost growth, fiscal tightness is impinging on that very growth impulse. In an ideal world, one would expect fiscal and monetary policy to be counter-cyclical and pull in the same direction. Instead, they have been horribly out of sync post-Lehman.

How did we get here?

So how did we get to a situation in which growth is at a decade-long low, but inflation expectations are in double digits and fiscal and monetary policy are so asynchronous?

The answer lies in two retrospective revisions that escaped much attention some weeks ago. The Central Statistical Organisation revised GDP growth up to 8.6 per cent in 2009-10 and a staggering 9.3 per cent in 2010-11.

There are two ways to interpret this. The charitable (but incorrect) interpretation is that India successfully decoupled from the global economy, returned to its nine per cent growth path post-Lehman, and it was only those pesky rate hikes subsequently that spoiled the party.

The more accurate interpretation is that these high growth rates are further confirmation of the laxity of fiscal and monetary policy post-Lehman that pushed the economy to grow beyond its potential and triggered off a three-year inflationary spiral, which culminated in growth slowing - sowing the seeds of the current asymmetry of fiscal and monetary policy.

Remember 2008? Between the farm debt waiver, sixth pay commission, and post-Lehman packages, the cyclically adjusted fiscal stimulus was a staggering 3.3 per cent of GDP. It's one thing to have a fiscal expansion of this magnitude in a country with a lot of slack, but quite another to have it in a supply-constrained economy such as India's.

What's even harder to understand is the glacial withdrawal of the stimulus. Remember asset sales only constitute an exchange of assets between the public and private sectors. They are not contractionary such as a tax or duty. Any evaluation of fiscal policy must, therefore, adjust for asset sales. By March 2011 - two and a half years after Lehman - 70 per cent of the Lehman stimulus was still in the system. The central government deficit - net of asset sales - was at a whopping 6.6 per cent of GDP vis-à-vis 3.9 per cent pre-crisis.

Monetary policy cannot escape culpability either. Even though rates were raised from 2010, real interest rates were still negative a year later. No wonder growth accelerated past nine per cent in the first quarter of 2011, output gaps surged and inflation was in double digits. This wasn't organic growth, but an economy on policy steroids.

Imperfect substitutability of policy

The RBI stepped on the gas in 2011, but the deficit missed Budget targets by a whopping 1.3 per cent of GDP and inflation stayed near double digits through 2011.

Not only does this reveal the disconnect between fiscal and monetary policy, but it also highlights the larger issue of imperfect substitutability between monetary and fiscal policy. Often, particularly in emerging markets with their institutional and regulatory rigidities, monetary policy has to overcompensate to offset the economic impacts of fiscal policy. Take the case of India. With a large fraction of consumption non-leveraged, interest rates only have an indirect impact on consumption. Monetary policy, therefore, needs to be tightened disproportionately to squeeze consumption by first having to choke income growth.

Similarly, with investment impeded by institutional bottlenecks (land, clearances, raw materials), rates would need to be slashed to generate any meaningful pickup in investment.

Furthermore, with limits on foreign participation in rupee-denominated bonds, exchange rates are disproportionately driven by equity flows. As such, rate cuts typically end up strengthening the currency and thereby partially offsetting the initially monetary impulse.

All told, monetary policy cannot seamlessly compensate for fiscal policy. This was in full view post-Lehman. Monetary policy was likely forced to over-compensate for the loose fisc, leading to greater demand destruction and deadweight losses than if policy had been co-ordinated.

The ratings scare

Eventually tight monetary policy began to bite and compounded the investment slowdown, driving growth all the way to 6.2 per cent. This was the straw that broke the camel's back, and ratings agencies promptly moved India to a negative outlook. The new economic team was then forced to slash spending to meet deficit targets. But, of course, this meant fiscal policy was strongly pro-cyclical and compounded the slowdown.

That, then, is the story of India's post-Lehman dizzying roller-coaster ride. Excessively lax policy that pushed the economy beyond its potential, and then a complete breakdown of policy co-ordination, which forced monetary policy to be excessively tight, demand destruction to be larger than needed, and eventually provoked a ratings scare forcing fiscal policy to be sub-optimally pro-cyclical. The upshot is that 2012-13 growth will be at a decade-long low.

Why is this relevant now?

Because we risk another breakdown in policy co-ordination. With the ratings threat alive, fiscal consolidation will need to be persevered with. But sustained tightening will continue impinging upon growth absent a goods and services tax or growth-induced tax buoyancy.

Predictably, there is growing market pressure on the RBI to be more dovish. The growing refrain is: "if fiscal policy is tightening, why can't monetary policy be loosened commensurately?"

But given the imperfect substitutability of policy, monetary policy would likely need to overcompensate and be dramatically loosened to offset the impact of a tightening fisc. The risks of reigniting inflationary and current account deficit pressures are clear. This would be a worrying replay of the lack of policy co-ordination post-Lehman - except in the opposite direction. Thankfully, the RBI has shown no inclination to follow this path yet.

So here's the bottom line: given our past excesses, the economy is in the midst of a much-needed macroeconomic adjustment. Austerity will hurt, but this is simply the price we have to pay to restore macro stability. Let's accept this. In this environment, forcing monetary policy to compensate is unlikely to be effective but dangerously counterproductive. More fundamentally, the last thing we need is another bout of asynchronous fiscal and monetary policy. The post-Lehman wounds are still too raw.

The writer is senior South Asia economist, JP Morgan

Disclaimer: These are personal views of the writer. They do not necessarily reflect the opinion of www.business-standard.com or the Business Standard newspaper

More From This Section

Don't miss the most important news and views of the day. Get them on our Telegram channel

First Published: Mar 31 2013 | 9:30 PM IST