38 Londres Street: The case of Augusto Pinochet and the art of impunity

Impunity is the central theme of 38 Londres Street, a marvellous and absorbing new book by the British-French lawyer and author Philippe Sands

)

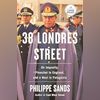

38 LONDRES STREET: On Impunity, Pinochet in England, and a Nazi in Patagonia

Listen to This Article

38 LONDRES STREET: On Impunity, Pinochet in England, and a Nazi in Patagonia

by Philippe Sands

Published by Knopf

453 pages $35

On March 3, 2000, after an airplane carrying General Augusto Pinochet landed in Santiago, Chile, his entourage pushed him in a wheelchair onto a mechanical lift as he smiled at the jubilant scene before him. Pinochet, the dictator of Chile from 1973 to 1990, had been detained in Britain while his lawyers fought attempts to extradite him to Spain, where a judge had issued an international arrest warrant for human rights violations committed by his regime.Also Read

After nearly 17 months, the British government eventually abandoned extradition proceedings; the 84-year-old Pinochet, who had been staying under house arrest just outside London, was deemed too ill to face charges in Spain. Yet upon his return to Chile, the old general appeared to be in robust health, standing up once his wheelchair touched the tarmac to give a military colleague a hearty embrace.

Years later, a woman whose husband was disappeared in 1974 remembered a broadcast of the moment as if it showed someone literally getting away with murder: “I felt consternation and rage, and a deep sense of impunity.”

Impunity is the central theme of 38 Londres Street, a marvellous and absorbing new book by the British-French lawyer and author Philippe Sands. In 1973, Pinochet and the Chilean military overthrew the democratically elected government of President Salvador Allende and proceeded to crush opposition and dissent, unleashing state-sanctioned sadism as a means of both retribution and deterrence.

The title of Sands’s book is the address that used to serve as headquarters for the Socialist Party in Santiago, before it became one of the military dictatorship’s centres for torture and disappearance. Sands calls the proceedings against Pinochet “the most significant criminal case since Nuremberg.” Never before had a former head of state been arrested in another country for international crimes.

Sands was incidentally connected to these events in several surprising ways. When Pinochet’s legal team tried to hire him, Sands’s wife threatened a divorce if he took the case. Decades earlier, his wife’s father, a publisher, happened to be working on a book proposal with Orlando Letelier, a former official in the Allende government, when Letelier was assassinated by Pinochet’s secret police. And in the course of researching this book, Sands learned that Carmelo Soria — a United Nations official who was abducted in Santiago in 1976 and whose body was found in a canal two days later — was his wife’s distant cousin.

But it is Sands’s connection to the other narrative thread in 38 Londres Street that gives this book its inimitable shape. In 1962, more than three decades before Pinochet was arrested in London, a man by the name of Walther Rauff was arrested in Punta Arenas, in Chile, and faced extradition to West Germany. Rauff, a former Nazi SS commander, oversaw the development of mobile gas vans, a precursor to the death camps. Sands learned that his mother’s cousin Herta, was most likely one of the thousands murdered in Rauff’s vans. Herta was 12 years old.

After World War II, Rauff escaped to Ecuador, where he met Pinochet, and for a time their families became close. In addition to their virulent anti-communism, the men shared an interest in Nazism. Rauff, who after his arrest lived in fear of the extradition that never came, was thrilled by Pinochet’s coup. As he bragged in a letter to a nephew, “I am protected like a cultural monument.”

The book moves back and forth in time, as Sands tracks down documents and people to interview, trying to ascertain if rumours about Rauff were true. Was Rauff involved with Pinochet’s secret police? Did he help design a Chilean concentration camp whose design bore an uncanny resemblance to Auschwitz?

Rauff worked at a seafood canning company, packing the flesh of king crabs into tins; the old Nazi became such a notorious figure in Chile that he featured as the sinister “man in Punta Arenas” in Bruce Chatwin’s In Patagonia. In 1965, the Chilean poet Pablo Neruda wrote an article attacking his country’s Supreme Court for allowing a war criminal like Rauff to live freely: “It protects people who efficiently organize collective murder and transport in vans.”

38 Londres Street is the third book in a trilogy that Sands began with East West Street (2016) and continued with The Ratline (2021). All three books revolve around big questions about evil, state power, immunity and impunity. But Sands is also a consummate storyteller, gently teasing out his heavy themes and the accompanying legal intricacies through the unforgettable details he unearths and the many people — Rauff’s family, former military conscripts, British legal insiders — who open up to him.

There is a measure of hope in this book, but Sands shows that even in the face of overwhelming evidence, justice is never a foregone conclusion. In the epilogue, a Pinochet confidant tells Sands that the Pinochet Foundation received a check for nearly 980,000 pounds from the British government, made out to Pinochet personally, to reimburse his expenses while he was in London. Pinochet’s critics were aghast, but his lawyer was unapologetic. “That’s the system,” he said.

The reviewer is non-fiction book critic for The Times ©2025 The New York Times News Service

More From This Section

Topics : Book Reviews Book Literature

Don't miss the most important news and views of the day. Get them on our Telegram channel

First Published: Oct 05 2025 | 10:43 PM IST